Low-Tech Kicks: Why The Humble Tennis Shoe Will Always Be In Fashion

One hundred and twenty years ago this year, one Charles Taylor was born. Taylor, a one-time basketball player, had been a shoe salesman for most of his life. And yet his legacy was to establish a multi-billion dollar industry. During the 1930s, in one of the earliest instances of celebrity sponsorship, Charles, better known as ‘Chuck’, lent his name to a minimalistic high-top basketball boot that had been launched in 1917. And the result – the Chuck Taylor All-Star – was arguably the first classic, must-have sneaker.

It is, if you like, the 501 of footwear: uncluttered, travelling well and getting better with age. It’s still around, still defining eras. During the 1990s, in a reaction against the day-glo, outlandish sneaker style that had become so much part of fashion, it was ‘chuckies’ that helped to signal the anti-establishment leanings grunge and a new EMO punk. As for the new millennium? Thanks to the general trend for dressing down, sales are at an all-time high, with some 200,000 pairs estimated sold. And that’s every day.

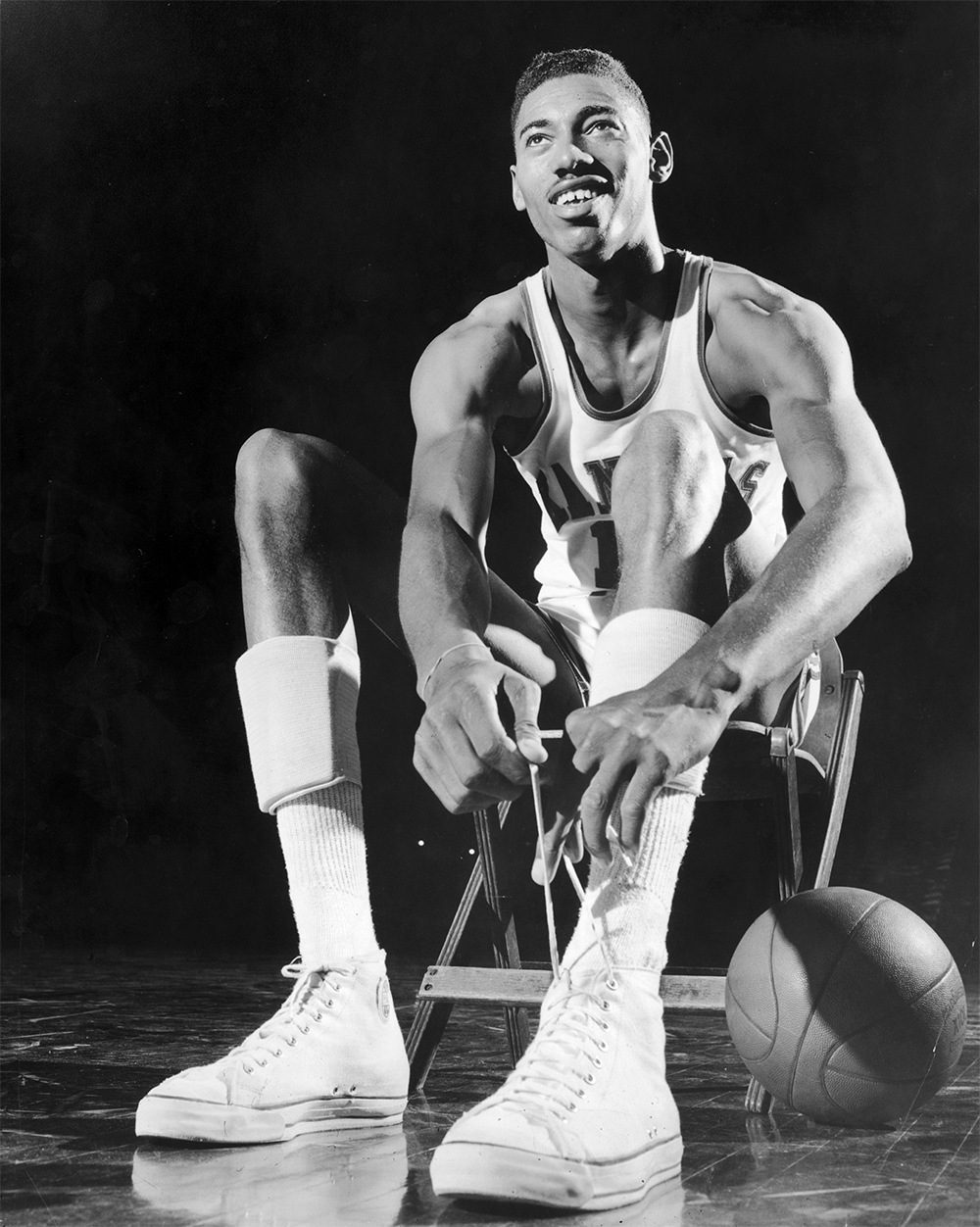

Wilt “the stilt” Chamberlain who played at the University of Kansas. He went on to score 100 points in an NBA game as a pro. And wore Converse

For all that their adoption beyond the athletic arena was driven firstly by comfort, and only then by cool and collectibility, sneakers have rarely been off the radars of either sports technology or pop culture. Arguably this goes back to 1978, when Bill Bowerman paid $10 to a local graphic artist to design a ‘swoosh’ logo as part of his plan capitalise on the new craze for jogging, and started a design revolution for ever-more bold, futuristic trainer designs.

Indeed, the common conception of the sneaker today – a term not coined until the mid 20th century, by ad man Henry McKinney, for the soundless steps one could take with a pair on – is typically something aggressive, colourful, pumped up and preening, such that it can be hard to imagine there was a time when it, the trainer or, more simply still, the humble plimsoll, was a much less flashy, more utilitarian, wear-it-until-it-falls-apart product.

And yet, arguably, it’s the more the stripped-back, less athletic take on this style of footwear that makes for the true design icons. This is perhaps because tech – or the look of tech – dates fast, or perhaps because simplicity goes with everything. Not for nothing have the sneaker giants that are Nike and Adidas enjoyed a 21st century renaissance in part through re-imaginings and re-issues of their more understated archive styles, be that the Blazer or Stan Smith.

The Adidas Stan Smith remains a timeless, iconic sneaker silhouette to this day

Count among these classic plimsolls not just the Converse All Star, or its skate-inspired Skid Grip, but the similarly endlessly copied likes of Vans’ Old Skool and Authentic, military PT styles from Novesta, Dunlop’s Green Flash, nautical looks such as Sperry’s Topsider CVO (that’s Canvas Vulcanised Oxford) – designs all pre-dating the 1960s – or modern interpretations of these from Japanese (of course) brands including Shoes Like Pottery and Wakouwa.

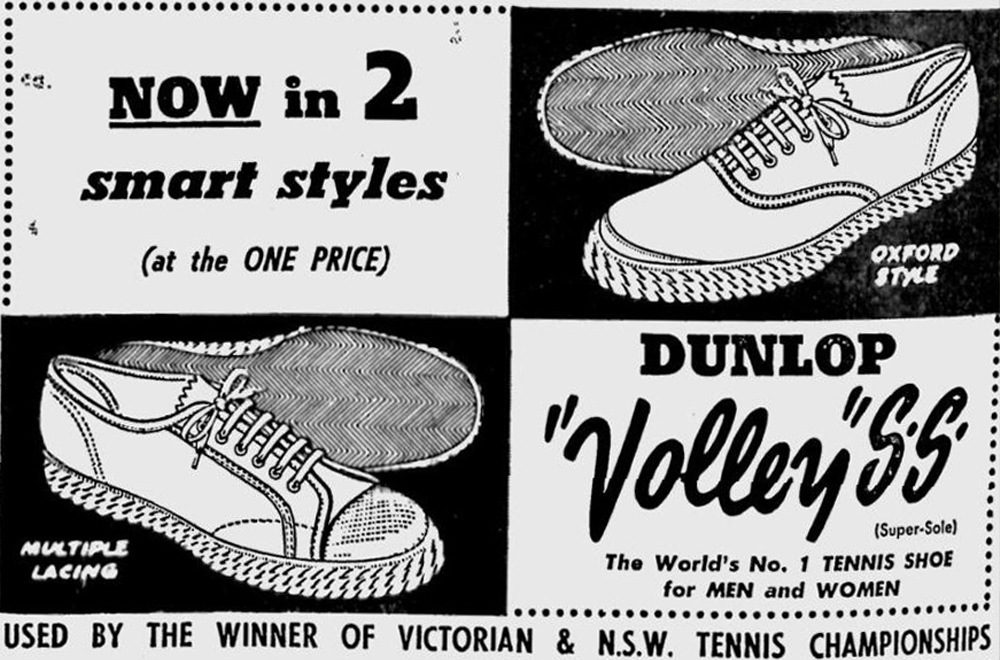

In fact, the basic look of these styles may have been tweaked for specialist use, be that wear on deck or with your deck, but really isn’t that much changed since the 1890s. That’s when the Liverpool Rubber Company – later acquired by Dunlop – created its ‘sand shoes’, ideal for wearing at the newly popular holiday destination that was the British seaside, with the tough canvas upper sealed onto a soft rubber sole by way of a rubber strip. Hence their nickname, ‘plimsolls’, after the plimsoll line, painted alongside ships after the 1870s to indicate their maximum loading capacity.

An advertisement for Dunlop ‘Sand Shoes’

Other companies with interests in rubber, like Goodyear, the tyre manufacturer, soon followed suit; so many, in fact, that in the US in 1908 some 30 of them were consolidated into the US Rubber Company. In 1917 they put their combined effort into the launch of Keds; ‘Peds’ had been the name wanted – after the Latin for ‘foot’ – but that was already taken. This was the same year, of course, that Converse’s All Star was launched too, meaning they jointly take the title for being creating the first named sneaker styles.

The utility and ease of these – at a time when, come rain or shine, most men wore hob-nailed boots – quickly became apparent, and not just in various sports, which were fast growing into popular past-times as much for the working as the leisure classes. In an early example of marketing spin, different grips were offered for different uses – be that tennis or yachting. But they clearly suited so many occasions – Robert Scott even packed pairs for his first Antarctic expedition, while various militaries adopted them for the physical fitness training of their troops.

The Converse All Star is now available in a kaleidoscope of colourways

In fact, the plimsoll was lauded for its very ordinariness – such that the All-Star, for example, was only available in one colour, black, until the late 1940s. It was then that Converse threw caution to the wind and introduced the style in… white. It would be another 20 years before a few more colours were introduced, an indication of the need to keep up with a changing world, one that increasingly saw the sneaker as a fashion item, one that was leaning towards the more bells and whistles approach to sneaker design that was just around the corner.

But if the plimsoll may have been down – in 2001 Converse had to file for bankruptcy – it certainly wasn’t out. What does it say that, two years later, in 2003, Converse was acquired by Nike – that the originator of sneakers with air pockets, space-age mesh uppers, self-lacing systems and claims to being the bounciest and lightest, saw value in a maker of basic canvas and rubber plimsolls that had barely changed in a century?